|

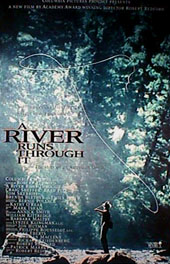

A River Runs Through It

Norman Maclean |

|

|

As a Scot and Presbyterian, my father believed that man by nature was a mess and had fallen from an original state of grace. Somehow, I developed an early notion that he had done this by fallen from a tree. As for my father, I never knew whether he believed God was a mathematician but he certainly believed God could count and that only by picking up God's rhythms were we able to regain power and beauty.

If our father had had his say, nobody who did not know how to catch a fish would be allowed to disgrace a fish by catching him.

My father was very sure about certain matters pertaining to the universe. To him, all good things - trout as well as eternal salvation - come by grace and grace comes by art and art does not come easy.

Undoubtedly, our differences would not have seemed so great if we had not been such a close family. Painted on one side of our Sunday school wall were the words, God Is Love. We always assumed that these three words were spoken directly to the four of us in our family and had no reference to the world outside, which my brother and I soon discovered was full of bastards, the number increasing rapidly the farther one gets from Missoula, Montana.

We held in common one major theory about street-fighting - if it looks like a fight is coming, get in the first punch. We both thought that most bastards aren't so tough as they talk - even bastards who look as well as talk tough. If suddenly they feel a few teeth loose, they will rub their rubs, look at the blood on their hands, and offer to buy a drink for the house. "But even if they still feel like fighting," as my brother said, "you are one big punch ahead when the fight starts."

It is not in the book, yet it is human enough to spend a moment before casting in trying to imagine what the fish is thinking, even if one of its eggs is as big as its brain and even if, when you swim underwater, it is hard to imagine that a fish has anything to think about. Still, I could never be talked into believing that all a fish knows is hunger and fear. I have tried to feel nothing but hunger and fear and don't see how a fish could ever grow to six inches if that were all he ever felt.

Below him was the multitudinous river, and, where the rock had parted it around him, big-grained vapor rose. The mini-molecules of water left in the wake of his line made momentary loops of gossamer, disappearing so rapidly in the rising big-grained vapor that they had to be retained in memory to be visualized as loops. The spray emanating from him was finer-grained still and enclosed him in a halo of himself. The halo of himself was always there and always disappearing, as if he were candlelight flickering about three inches from himself. The images of himself and his line kept disappearing into the rising vapors of the river, which continually circles to the tops of the cliffs where, after becoming a wreath in the wind, they became rays of the sun.

It is a strange and wonderful and embarassing feeling to hold someone in your arms who is trying to detach you from the earth and you aren't good enough to follow her.

I called her Mo-nah-se-tah, the name of the beautiful daughter of the Cheyenne chief, Little Rock. At first, she didn't particularly care for the name, which means, "the young grass that shoots in the spring," but after I explained to her that Mo-nah-se-tah was supposed to have had an illegitimate son by General George Armstrong Custer she took to the name like a duck to water.

One reason Paul caught more fish than anyone else was that he had his flies in the water more than anyone else. "Brother," he would say, "there are no flying fish in Montana. Out here, you can't catch fish with your flies in the air."

Something within fishermen tries to make fishing into a world perfect and apart - I don't know what it is or where, because sometimes it is in my arms and sometimes in my throat and sometimes nowhere in particular except somewhere deep. Many of us probably would be better fishermen if we did not spend so much time watching and waiting for the world to become perfect.

The hardest thing usually to leave behind can loosely be called the conscience.

One of life's quiet excitements is to stand somewhat apart from yourself and watch yourself softly becoming the author of something beautiful, even if it is only a floating ash.

Poets talk about "spots of time," but it is really fishermen who experience eternity compressed into a moment. No one can tell what a spot of time is until suddenly the whole world is a fish and the fish is gone. I shall remember that son of a bitch forever.

If you have never seen a bear go over the mountains, you have never seen the job reduced to its essentials. Of course, deer are faster, but not going straight uphill. Not even elk have the power in their hindquarters. Deer and elk zagging and switchback and stop and pose while really catching their breath. The bear leaves the earth like a bolt of lightning retrieving itself and making its thunder backwards.

I said, "I know he doesn't like to fish. He just likes to tell women he likes to fish. It does something for him and the women. And for the fish too," I added. "It makes them all feel better."

I sat there and forgot and forgot, until what remained was the river that went by and I who watched. On the river the heat mirages danced with each other and then they danced through each other and then they joined hands and danced around each other. Eventually the watcher joined the river, and there was only one of us. I believe it was the river.

As the heat mirages on the river in front of me danced with and through each other, I could feel patterns from my own life joining with them. It was here, while waiting for my brother, that I started this story, although, of course, at the time I did not know that stories of life are often more like rivers than books. But I knew a story had begun, perhaps long ago near the sound of water. And I sensed that ahead I would meet something that would never erode so there would be a sharp turn, deep circles, a deposit, and quietness.

You have never really seen an ass until you have seen two sunburned asses on a sandbar in the middle of a river. Nearly all the rest of the body seems to have evaporated. The body is a large red ass about to blister, with hair on one end of it for a head and feet attached to the other end for legs.

"Help is giving part of yourself to somebody who comes to accept it willing and needs it badly. "So it is that we can seldom help anybody. Either we don't know what part to give or maybe we don't like to give any part of ourselves. Then, more often than not, the part that is needed is not wanted. And even more often, we do not have the part that is needed. It is like the auto-supply shop over town where they always say, 'Sorry, we are just out of that part.'" I told him, "You make it too tough. Help doesn't have to be anything that big." He asked me, "Do you think your mother helps him by buttering his roll?" "She might," I told him. "In fact, yes, I think she does."

"Tell me, why is it that people who want help do better without it - at least, no worse. Actually, that's what it is, no worse. They take all the help they can get, and are just the same as they always have been."

To my father, the highest commandment was to do whatever his sons wanted him to do, especially if it meant to go fishing.

Big clumsy flies bumped into my face, swarmed on my nose and wiggled in my underwear. Blundering and soft-bellied, they had been bornbefore they had brains. They had spent a year under water on legs, had crawled out on a rock, had become flies and copulated with the ninth and tenth segments of their abdomens, and then had died as the first light wind blew them into the water where the fish circled excitedly. They were a fish's dream come true - stupid, succulent, and exhausted from copulation. Still, it would be hard to know what gigantic portion of human life is spent in this same ratio of years under water on legs to one premature exhausted moment on wings.

I took one look at it [fly] and felt perfect. My wife, my mother-in-law, and my sister-in-law, each in her somewhat obscure style, had recently redeclared their love for me. I, in my somewhat obscure style, had returned their love. I might never see my brother-in-law again. My mother had found my father's old tackle and once more he was fishing with us. My brother was taking tender care of me, and not catching any fish. I was about to make a killing.

"Help is giving part of yourself to somebody who comes to accept it willingly and needs it badly."

A fisherman, though, takes a hangover as a matter of course - after a couple of hours of fishing, it goes away, all except the dehydration, but then he is standing all day in water.

When I was young, a teacher had forbidden me to say "more perfect" because she said if a thing is perfect it can't be more so. But by now I had seen enough of life to have regained my confidence in it.

"All there is to thinking is seeing something noticeable which makes you see something you weren't noticing which makes you see something that isn't even visible."

On the Big Blackfoot River above the mouth of Belmont Creek the banks are fringed by large Ponderosa pines. In the slanting sun of late afternoon the shadows of great branches reached from across the river, and the trees took the river in their arms. The shadows continued up the bank, until they included us.

"... but you can love completely without complete understanding."

Now nearly all those I loved and did not understand when I was young are dead, but I still reach out to them.

Eventually, all things merge into one, and a river runs through it. The river was cut by the world's great flood and runs over rocks from the basement of time. On some of the rocks are timeless raindrops. Under the rocks are the words, and some of the words are theirs.

|